With everything I’ve read about the occupy movement’s stance on leaderless, disorderly, unspecific action it would seem like it is crumbling before our eyes, but this is not the case – it is being refined. Critics tend to support the message against giant corporate rule of politics like most people aware of the movement (70% last I checked) but are wary of the tactics that are either too scary or incapable of making “real change.” Many are baffled as to why this “whole movement” can’t organize into a concrete program with a declaration of demands, or find some way onto the negotiation table, instead of letting the wave of outrage fizzle out. Such a view misses the revolutionary character of this movement that got so many people mobilized in the first place; no one goal or defined set of goals can be established because the shared sense out on the streets (as opposed to in a warm house) is that corruption in the present can’t be localized – it is systemic.

Before I elaborate on what that means I just want to point out that occupying has a long history as a tactic and though I (and just about everyone else) refer to a single movement, this is more of a method for putting bodies in a physical space than a unified group of activists. This inability to understand the logic and motivation of occupying by people not involved is the greatest danger to making the “real,” “positive” change that is necessary today. The very idea of a unified occupy movement – an entirely unfractured cohesive whole – carries along with it certain risks, risks which outweigh the potential diminishing of mass support from the “general public.”

As both a camper who left his house to occupy Oakland for nearly two months and is a consistent participent in the General Assembly to this day, I can truthfully state that occupiers disagree and argue to such an extent that the whole we speak of is nothing beyond the sum of multiple autonomous action groups, committees, caucuses, and people. The non-hierarchical structure and the aversion to negotiating with existing powers are part of the originality of this movement – its lifeblood – to take another direction forcing all members to follow would effectively kill it. The arguments that take place at GAs, encampments, and rallies/marches are of such a grand politico-philosophical significance that they end up polarizing those involved; this is not a problem however when dissenters of an action can simply walk away. It’s the convenience of occupy actions that all of it’s members need not be on board with what happens, and personal agendas remain just that: personal (or autonomous). You can come along for the ride or opt-out, but there is no line drawn in the sand as to where you stand beyond the action taken. This makes saying one is an ‘occupier’ somewhat of a dubious claim: what it means is as various as the number of people you talk to.

General Assemblies do pass and reject proposals that become endorsed as official occupy proposals and full consensus is celebrated, but often one person will vote ‘nay’ when facing imminent consensus on principle. Even proposals that aren’t passed give smaller groups ideas to work with in the future and connect interested individuals together. Existing activist groups also get an opportunity to widen their base and plug passionate bodies into their on-going work. In practice I see the GA as a hub to link people into groups of all kinds along with a center stage where speakers can use their rhetoric to attempt to persuade those in attendance. This body does not govern or direct, it is an experimental zone facilitating future actions and giving ideas with people behind them a chance to converge and compete. The 99% vs. the 1% narrative is a powerful one, but it is utterly ridiculous to attempt to to get 99% of a population to all agree on actions, principals for actions, and goals without marginalizing a big chunk.

The impulse to pull activity deemed outside of or illegitimate back into the general assembly to go through the consensus process can bog down efforts move forward with positive action and speedy mobilization. There is a strong resentment against a slow moving beauracracy by those who see committee organizers for hampering direct action. Such a move towards unification of all actions that employ occupying as a tactic or a symbol might be reflecting the rhetoric of a news reporter/zombie t.v. news watcher who is thoroughly enmeshed in mainstream society. They want to have a dialogue, but our answers don’t translate into categories they understand; we cannot speak as a whole and crystallize ourselves into a position with which to make demands or define ourselves. Ask someone what occupy is about and you’ll get as many different responses as people you ask; it’s not one thing it’s everything.

As for the systemic injustice claim, this is where the greatest divide comes in: revolution or reform? The genuine fright that people feel at the prospect of violent revolution is understandable, especially considering fascist, communist, and other populist uprisings in the past few hundred years that seek a total overhaul of the means of production. These surgical revolutions that aim for the head of the state and then implement their own vision for how a “just society” should be run are totally misguided in my opinion. However, the anti-vanguardist, insubordinate sentiment of occupiers keeps these theories from galvanizing people into a class/nation to wage warfare with another class/nation; the disorderliness and bickering actually keeps any one theory, ideology, leader, strategy (pick one) from forcing a spectacular revolution which would shed more blood than we could bear. I think the energy of this movement from the young and future-less (banished to debt slavery with only mindless jobs available) is aware of these dangers and this, perhaps along with the individualist culture we were sold, accounts for the stubborn rejection of official leadership.

The revolution as a great resounding event must be guarded against, but the revolutionary spirit, as opposed to the spirit of reform, is absolutely necessary. As we’ve all heard from the 99%ers: the banks are so powerful, corporations are so integrated in politics, the prisons are so full (and someone profits), and basic services (health, food, housing) are so hard to provide that this is a systemic problem and a revolutionary attitude is desperately needed. As I like to gloss it: the powers that be have gotten too big – the market forces are more powerful than the state, and the state has to play catch up to prevent a global collapse. Now (as before but more so), we get banks that freely commit fraud and make profits from complex equations, interest rates, and inflation – and it continues because they’re too big? This latest crisis in capitalism or a foreseeable one down the road (because, you know, it’s supposed to be normal now to have a crisis) could lead to a reaction on par with any violent revolution of the past, and this fact we are faced with ought to encourage people that we cannot go on this path without a revolutionary shift in the way we collectively relate, exchange, and produce stuff with each other.

A revolution can take place as a subtle shift in thinking and operating which would seem impossible to past generations. Rather than opting for full-blown class warfare (which might be only just as bad as a hot, flooded planet of starving wage laborers… which in some sense it already is), occupiers are making the change they want to see with the world. The tent cities can be seen as protests but also blue-prints for what a community could look like that does not enslave so many people, nations, animals, or whatever. A reform in line with occupy principles like, say, ending corporate personhood would be a real gain but the other dozens of atrocious, corrupt laws and practices would go on as the next oblivion facing the prey of the 1% looms. Chanting about how another world is possible and then building up a community where it’s people provide basic services for each other is revolutionary because communities are so scarce these days.

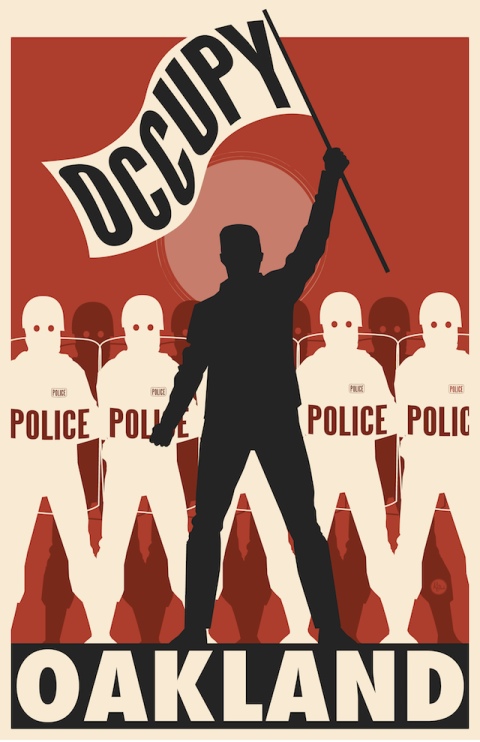

The leaderless rejection of hierarchy and the disorganization of certain occupies helps ward off both vanguardist parties and reformers who would settle for piecemeal change in a world headed for (and in some ways inside of) the abyss. Considered by political “realists” an obstacle for progress, this is actually the unique vitality the movement – along with its critical-activist spirit and the simple brilliance of the idea ‘occupy’: bringing back physical bodies into their own space. This vitality gravitates scattered individuals together to organize and make collective decisions to then act on both outside and inside the commune. The energy is there, the ideas are there, the model for life after capitalism is there; the only thing holding us back is police oppression.

What an elitist point of view! Occupy’s energy, you write, comes “from the young and future-less.” Theirs is a “shared sense out on the streets (as opposed to in a warm house) that corruption in the present can’t be localized—it is systemic.”

“The energy is there,” you go on, “the ideas are there, the model for life after capitalism is there; the only thing holding us back is police oppression.”

Obviously, your model excludes most Americans. How many of us feel oppressed by the police? It might be 9%, but it certainly isn’t 99%.

And how many of us live on the streets? The most recent data (for 2008-09) presented in the latest National Alliance to End Homelessness report (11 Jan 2011) shows the majority of America’s homeless are in fact sheltered. Only 40% live on the street, in a car, or in another place not intended for human habitation. In 2009, the total number of unsheltered homeless (252,821) amounted to < 8.2% of our national population.

So 91.8% of us do not live on the street and therefore, according to your reverse snobbism, do not share street people's magically intuitive sense that corruption is systemic.

As long as Occupy continues to suffer such exclusionist, willful delusions, it will remain a failed movement.

CORRECTION: Math was never my strong suit. The figure should be 0.08% not 8.2%. So 99.92% of us do not live on the street. I understated my own argument.

Alan,

When I write about the revolutionary energy of the occupy movement I believe the youth play a crucial role in keeping it going. Though many don’t stay out there on the streets 24-7 some do, the “shared sense out on the street” does not refer to homeless people but those marching, rallying, and risking arrest in the streets. It was admittingly a little vague, but the sentence above you quoted was in the context of demands and organization, not who is a “real” occupier (like homeless people).

Your stats may dazzle onlookers, but those who feel oppressed by the police certainly include those living in a house (but homelessness is de facto unlawfull in many cities which is a travesty). Also, homeless shelters aren’t the answer and don’t always stabilize a family or persons needs, and the number of these people is growing with all the foreclosures.

I honestly don’t find it necessary to include 99% of Americans in every analysis I do. Has it become elitist now to not account for all of the 99% when speaking of police oppression? I maintain that minority groups feel police enforcement the worst, and I certainly don’t think this is an elitist position.

Hey BillRoseThorn.

I am an advocate for the homeless and believe that the homeless are the core, the heart of the occupy movement. I have been homeless off and on much of my adult life and have lived on the street, in shelters, in rehab and back-to-work programs, and have learned through direct experience that the human services sector of federal, state and city governments are structured to profit off the homeless on an industrial scale, and are, apart from some philanthropic donations, paid for by the taxpayer.

The homeless are the core of the occupy movement because they are the ones who have been marginalized and discarded and are then input into what I call the Homeless Industrial Complex, which, along with the Prison Industrial Complex and the Psychiatric Industrial Complex, form a circular conveyor belt designed to keep millions of citizens in check within profitable bureaucracies that are parasitic by nature, even as they earn huge profits for their owners and functionaries. Few ever escape unscathed, just as citizens convicted of felonies cannot vote in most states, most clients of the Homeless Industrial Complex are stigmatized for life and are tracked by their SS # as suspect citizens for the rest of their lives. Try getting a corporate job after living in a shelter or being admitted into a psych unit, you cannot even purchase a gun in most states, a telling fact in a gun-crazy culture…

This is why I advocate for the inclusion of the homeless and street people at every level, if we cannot work with those who need help as well as those who have more to give and contribute, what is the point? There are so many myths and misconceptions about the homeless promulgated by the Corporate State, we are not mostly criminals or drug addicts or mentally ill; we are also single mothers with children and old folks and sofa surfers, and, more and more, those who were foreclosed against. Even the homeless citizens (and illegal immigrant homeless, of course) who are criminals, drug addicts, or mentally ill have much to give and contribute, as they possess a wealth of skills and life experience that can be invaluable, we need only trust and include them, take a chance on them, and if occupy gets burned on an individual level by some homeless folks, hell, we get burned by domiciled opportunists and takers too!

The homeless are occupy’s natural base. I am proud I was homeless and may, the way the economy is going, become homeless again. Only the very wealthy these days who prepare properly are safe against becoming homeless anymore, and those of us who still support ourselves and pay our bills and have a roof over our head we pay for must remember that the homeless men and women on the street and in the facilities of the Shelter Industrial Complex are our brothers and sisters. We should never blame them for giving the police an excuse for cracking down, never let the authorities divide and conquer us, never let the authorities convince us that we are better than our homeless brothers and sisters because once we do, it is over and we are no better than those who convince us to discriminate against ourselves…

Thank you for this comment Michael J. Robinson, I agree almost entirely with what you wrote. I lived homeless for two months during the heydays of Occupy Oakland, and we were and still are the ones holding down the camps as physical bodies helping each other protest and live in our, public, space. Though I’ve moved indoors in January, I continue to support and actively engage with those on the ground level. What you write about the myths circulating about homelessness and the marginalization of those without a home by the Corporate State is the truth. The Psychiatric Complex also deserves attention for mislabeling ‘mental disorders’ – a very problematic term – and determining what is ‘normal’ and ‘pathological’.

I only try to avoid saying who the ‘core’ of the occupy movement is so as not to exclude other groups, which is not to say everyone (or even 99%) needs to be represented here.